Baltimore, Md.

Diana Press

12 West 25th Street

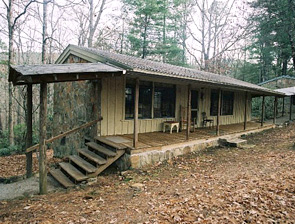

First housed in this brick building in Baltimore, Diana Press was one of the earliest lesbian-feminist publishing companies in the country. Established in the mid-1970s, it was committed to publishing openly lesbian material, which was not available from mainstream houses. Before she became a mass-market star with Rubyfruit Jungle, Rita Mae Brown published her collections of lesbian poems, Songs to a Handsome Woman and The Hand That Cradles the Rock, and a volume of essays, Plain Brown Wrapper, with Diana Press. Other titles from Diana included Elsa Gidlow’s Sapphic Songs and Judy Grahn’s True to Life Adventure Stories, as well as early poetry by Pat Parker. In the late ’70s, Diana Press relocated to the San Francisco area. If not for the efforts of this pioneering press, along with Naiad Press, Persephone Press, Daughters Inc., and many others, a lot of openly lesbian writing would have never seen print. As a writer who is also a lesbian, I’m grateful.

You must be logged in to post a comment.