They’d gotten off on the wrong foot, and if Cam found out, there would be hell to pay. Ada needed this young man to know she wasn’t like other whites, the ones who touted their Confederate ancestors or acted like Jim Crow was still in force. She could have used the example of Miss Ruthie to explain away her cautious behavior, but it seemed like too elaborate a story, offered too late. Or she could have told him about the early days of integration at Central, but she had done so little—just interrupted one bullying incident.

So instead, she said, “I . . . I’ve read Mr. Baldwin,” just before he reached the library door. Cam had brought the novel Giovanni’s Room home from her trip to Washington, D.C. for the March. “It’s about two men who have an affair,” Cam had explained excitedly. “One white and one black.” The volume had made the rounds in their gay circle before ending up, tattered and well-read, on a high shelf in the bedroom closet.

“He’s a fine writer,” Ada said.

“One of the best,” Mr. Browne said, with a thin smile that suggested he might not hold a grudge.

In this excerpt from my historical novel, The Ada Decades, Ada Shook, a white school librarian in Charlotte, N.C. in 1970, has a run-in with a new teacher, Robert Browne – one of only two black faculty members in the school – about a book order. She worries that some of his choices, including books by Ralph Ellison, W.E.B. DuBois, and James Baldwin, will play badly with the conservative white parents in the school. Mr. Browne calls her on it, and she retracts her concern – but then wants him to know she’s not like “other whites.” A closeted lesbian, she’s read James Baldwin’s novel about an affair between two men in Paris.

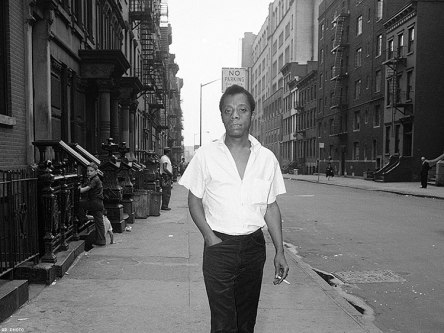

Baldwin on the streets of Harlem/AP photo

The work of James Baldwin (1924-1987) figures prominently in this chapter of my book; it becomes the subject of attempted censorship by parents at Ada’s school. I won’t give away what happens, but things get tense at the fictional Central Charlotte Junior High.

I re-read a lot of Baldwin’s nonfiction work as my novel was unfolding, especially Nobody Knows My Name, and I took one of the epigraphs for the book from him: “Love is a growing up.” I felt that so aptly summarized what I had learned about long-term relationships. There’s the tender romance in the early stages of “girl meets girl,” but a relationship over the long haul is so much more than that. It’s about working through problems and plowing through bad times as well as celebrating the joyous moments. I call The Ada Decades a love story for that reason – it’s about two women enduring together and building a life over time, despite the odds.

And more about Baldwin, whose writing is rightfully enjoying a revival: Efforts are underway to save the house in St.-Paul-de-Vence, France, where he lived for the last seventeen years of his life, and turn it into a retreat for writers and artists. As Shannon Cain wrote with regret in July 2016, “There exists no trace of James Baldwin in the village … His half-demolished house bears no plaque… Here in the place he considered home, it appears that this great American literary and civil rights icon has disappeared from history.”

If you haven’t seen the documentary I Am Not Your Negro, please run out and do so. I’ve seen it twice, and I will undoubtedly watch it again. James Baldwin has been gone for thirty years, but his wisdom speaks directly to this moment in American history.

Today is The Ada Decades’s official pub date, and it’s now available everywhere! Pick up a copy at your favorite bookseller.

Read Full Post »

You must be logged in to post a comment.