Twig drove her to The Hornet’s Nest, a bar in the basement of an old hotel in town. It wasn’t a homosexual club so much as a place where gay people gathered while the management turned a blind eye. Both women and men frequented it, and Cam had accompanied Auggie and Twig there many times, against Ada’s advice. The place seemed seedy, dangerous, with an entrance down a dark flight of stairs. “And what if you run into someone from school?” Ada had asked.

“I reckon they’ll be as scared to see me as I am to see them,” Cam replied.

The plot of my new novel, The Ada Decades, covers seventy years in the lives of LGBT people in Charlotte, N.C. In the above scene, which takes place in 1962, Ada goes (reluctantly) with her gay friend Twig to The Hornet’s Nest, one of several bars in Charlotte to “serve as ad hoc gathering spaces for the gay community,” according to Charlotte historian Josh Burford.

Before there were LGBT community centers, conferences, high school and college associations, bookstores, and choruses, bars served an important function in the lives of queer people. Even at the seediest bars, queer folks could meet each other for friendship and love, finding community when they might have feared they were alone.

As Burford notes, bars as community institutions laid “the groundwork for future activism.” For example, at Julius, a gay-favorite bar located on West 10th Street in New York City, gay men staged a “sip in” in 1966 to challenge a state law that prohibited serving alcohol to “disorderly” people—and just being gay was considered “disorderly” conduct. The June 1969 riots at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Sheridan Square, are generally credited as the start of the modern LGBT rights movement.

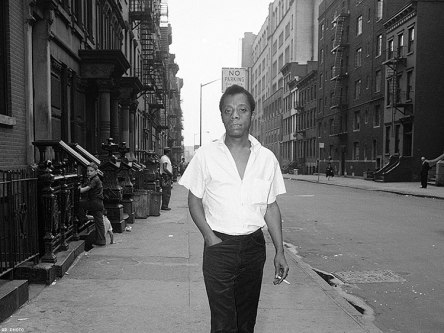

The “sip in” at Julius in Greenwich Village in 1966

The downside, of course, is that bars foster drinking, and habitual drinking can lead to alcoholism—a problem that our community has been tackling through LGBT-specific social services for 30+ years.

For more about my characters Ada, Cam, and Twig and their experiences as gay Southerners “back in the day,” pick up a copy of The Ada Decades at your favorite bookstore or online retailer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.