They had walked silently for one long block when Auggie broke into a happy trot and pointed with excitement. “There it is!” A sprawling frame bungalow, set back from the street and guarded by a majestic oak, came into view. With its modest height and lack of trim, it was not the peer of its neighbors, but Ada recognized its charm even if she didn’t understand Auggie’s excitement.

“It’s pretty,” she said.

“That, dear librarian, is where Carson McCullers lived, oh, twenty years ago,” Auggie said with a sigh. “She started writing The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter right there in that house.”

This scene takes place in the third chapter of my new historical novel, The Ada Decades. It’s 1958, and Ada Shook’s friendship with Cam Lively has been progressing since they bonded over the integration of the public school where they both work. But Cam would like it to go … well, further. She creates a book club that will get Ada to her apartment in the Dilworth neighborhood of Charlotte, N.C. – because, as their mutual friend Auggie, puts it when he spells it out for Ada: “How else do you get a librarian to come over and meet your friends? She would have preferred a softball team, that’s for sure.”

Everyone at the book club, it turns out, is queer – which both intrigues Ada and makes her nervous, because she hasn’t figured out what her feelings for Cam mean. Cam and her friends have created a social network in which they support each other – “family,” to use the code for LGBT people.

The Carson McCullers house is a real thing that still stands at 311 East Boulevard in Charlotte; it’s now a restaurant where a writer can have excellent Indian food while channeling her inner Carson. The Georgia-born author (1917-1967) and her husband, Reeves, a poet, lived there when they got married and moved to Charlotte in 1937, and it is, in fact, where she wrote the first chapters of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. Carson’s biographer, Virginia Spencer Carr, offers a detailed description of the large, furnished flat in her excellent book, The Lonely Hunter.

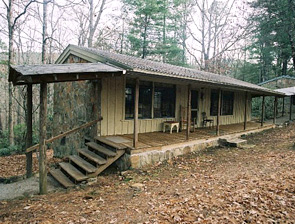

The house where Carson McCullers and her husband first rented an apartment in Charlotte is now a restaurant

The rent was too high, though, and within a few months they moved to an apartment at 806 Central Avenue, which is unfortunately no longer standing. Carr writes that Carson found that place too cold to work in and preferred to write at the Charlotte Public Library.

806 Central Avenue in Charlotte no longer exists

Carson was conflicted about her sexuality; she was enamored with several women, but likely never consummated the relationships. Her strongest ties were with gay writers and artists, and her identification with social and sexual outcasts figures prominently her fiction. “Carson has such a deep appreciation for freaks,” Auggie says to Ada in my novel.

Right now, you can get a copy of The Ada Decades at the Bywater Books website; after March 14, it will be available in paperback and e-book formats through bookstores and other online vendors.

You must be logged in to post a comment.