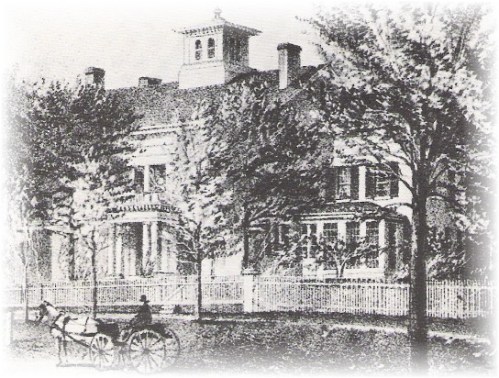

Baltimore, Md.

Gertrude Stein residence

2408 Linden Avenue (private)

Gertrude Stein’s (1874-1946) first ambition was not to be a writer, but a psychologist. After studying psychology with William James at Harvard, Stein was accepted at the John Hopkins Medical School, where her brother, Leo (with whom she was very close), was also enrolled. She lived with relatives at this address (on the National Register of Historic Places since 1985) for about a year, then moved in with Leo at 215 East Biddle Street.

Stein was unhappy and unfulfilled in medical school. She was also on the brink of discovering her lesbianism. While living in Baltimore, Stein ran with a lesbian crowd, a group of Bryn Mawr College graduates led by a young woman named Mabel Haynes. Sadly for her, Stein fell unrequitedly in love with Haynes’ “romantic friend,” May Bookstaver. The experience made a deep impression on Stein, whose first novel, Q.E.D., completed in Baltimore in 1903, was an autobiographical account of this lesbian love triangle.

Unlike most of Stein’s work, Q.E.D. was openly lesbian in content and language. Stein put the finished manuscript away for 30 years, and then, in 1932, unearthed it and showed it to her agent, who advised against trying to publish it because of its “controversial” theme. Q.E.D. was finally published in 1950, four years after Stein’s death.

Stein left Baltimore in 1903 to visit Leo, who had moved to Paris, and to try to forget May Bookstaver. Paris agreed with her, and she lived there the rest of her life, meeting Alice B. Toklas, her life companion, in 1907. And May Bookstaver and Mabel Haynes? They both pursued much more traditional lives, ending their affair and marrying men.