Independence, Kansas

William Inge Center for the Arts

Independence Community College

1057 W. College Avenue

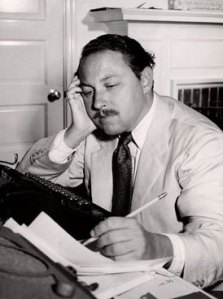

Included in this center’s collections are books, tapes, and records from the private cache of playwright William Inge (1913-1973), who attended college here and gave his original manuscripts to the school in 1969. Inge is best known for four successful Broadway plays that were subsequently made into films – Come Back, Little Sheba (1950), Picnic (1953 – won the Pulitzer Prize), Bus Stop (1955), and The Dark at the Top of the Stairs (1957). Also a screenwriter, Inge won an Academy Award in 1961 for the original script of Splendor in the Grass.

Inge was born and raised in Kansas, and all of his plays took that state as their setting. His boyhood home at 514 N. 4th Street is still standing (see above), and was the setting for The Dark at the Top of the Stairs. The home is owned by the William Inge Festival Foundation, and each year, playwrights-in-residence are selected to come to Independence to live in the house and write for nine weeks at a time.

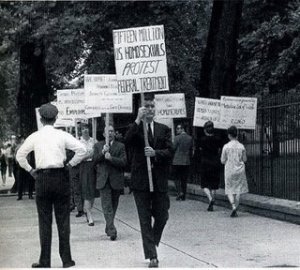

Inge’s work often focused on the repressed sexuality and stultifying social norms that he must have experienced in his own life. A closeted gay man and an abuser of alcohol, Inge included a few characters who were gays stereotypes in his later, lesser-known plays, written in the 1960s after his success had faded. His one act, “The Boys in the Basement,” dealt with a man’s discovery of his homosexuality and was his only play to address the topic directly. Sadly, Inge committed suicide at his home in Hollywood in 1973. He is buried in Independence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.