Lancaster, Pa.

The Demuth Museum

120 East King Street

Born at 109 North Lime Street in Lancaster, the artist Charles Demuth (1883-1935) moved at the age of 7 with his family to this location. Demuth’s family was wealthy, owning the oldest tobacco and snuff factory in the country; their tobacco shop was next door to their home.

Demuth suffered from a childhood disease that left him lame, and he spent several years confined to his bed. But he showed an early talent for painting, and as a young man, was able to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Later, he came under the aesthetic mentoring of gay artist Marsden Hartley. Inspired by Hartley’s work, Demuth developed a precisionist style of painting, and his depictions of modern city architecture are what many critics consider his greatest contributions.

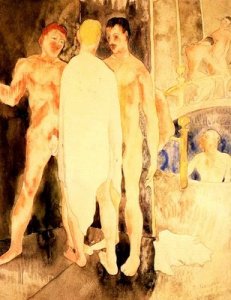

But gay critics are more interested in Demuth’s renderings of the early homosexual community in New York City. In 1918, Demuth accomplished a series of paintings depicting gay men at bathhouses in lower Manhattan (see above). Another group of paintings from 1930 bear names such as “Two Sailors Urinating” and “Three Sailors on the Beach,” and also have a strong gay sensibility. Even Demuth’s later still-life paintings of fruits and flowers are amazingly phallic.

According to one biographer, Demuth was more a voyeur of gay life than an active participant. He traveled in bohemian circles, frequented Mabel Dodge’s salon in New York, was an ancillary members of the Provincetown Players, and spent several summers rooming in Provincetown with Hartley. Eugene O’Neill patterned the sexually ambivalent Charles Marsden in his play Strange Interlude (1928) after the closeted Demuth.

Demuth’s home on King Street is now The Demuth Museum, but at the website, you’ll find scant reference to his homosexuality.

You must be logged in to post a comment.